Baptized Without Blood: Calling out Gender Essentialism in Modern Magic

By Emma Cieslik.

Gabrielle Cerince, Devotee of the Goddess, smeared period blood across her cheeks, then her forehead, then down her neck before licking her fingers. On July 2nd, 2023, Cerince shared a reel of this Blood Magic and Womb Ritual on Instagram. In patriarchal religious institutions and societies, Cerince explains during the video, period blood has been shamed by people who do not understand or accept it as sacred material culture. She painted her face to acknowledge that what is seen as socially and religiously disgusting and unnatural is truly divine.

Her goal to destigmatize period blood, however, highlights body witchcraft that reinforces the gender essentialism, racism, ableism, and queerphobia common among traditionalist Christian communities. Cerince, an acolyte on the Priestess Path and initiated Dianic witch with years of birthing experience, started her Instagram account @sacred.origins in March 2016 and currently has over 38,000 followers across the world. She is part of a growing movement of blood magic, a subculture of body witchcraft, in which devotees paint and pray with their own menstrual blood as a visual act of defiance. In doing so, they believe they are reclaiming pride in their womanhood through the celebration of menstruation and the ability to conceive.

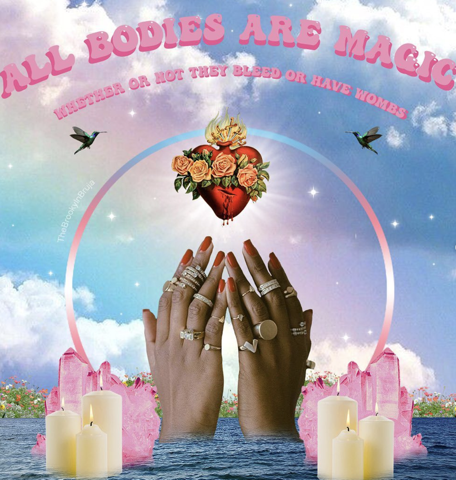

Trans, disabled, autistic artist Río Edén’s All Bodies Are Magic piece released on his Instagram account @thebrooklynbruja in Summer 2021.

Photo courtesy of Río Edén.

But there is an inherent problem, as trans, disabled, and autistic bruja Río Edén explains, when equating blood magic with womanhood. His art (featured above) was created in response to someone in the witch community who argued that the power and magic of witches comes directly from their wombs. Edén and many other practicing witches sought out witchcraft because of its sex-positive, LGBTQ+-affirming, and non-patriarchal beliefs. Yet, they may not have wombs, may not feel any connection to their wombs, and may not center their magical practice in their wombs. For Edén, as someone raised in an isolated and extremely homophobic Baptist then Pentecostal community, it felt like a part of his religious past had resurfaced.

Edén recalled Christian churches, conversion therapists, and his family dictating the way that everything had to be: gender normative, performatively heteronormative, and explicitly transphobic. He believes that it is perfectly acceptable for someone to personally feel that their womb, their period, or their genitalia are magical, but using the terms “it is” to declare a universal fact is different and harmful, especially for queer people seeking spiritual refuge and meaning in witchcraft. “I think that all bodies are magical,” he explained. “All bodies contain the same amount of magic regardless of what they’re anatomy is, whether they have certain genitalia or certain reproductive organs.”

His experience is not isolated and not new. In fact, Regina Smith Oboler explored gender essentialism in the Contemporary Paganism community in 2010. As Oboler noted, the community originally had a strong gender essentialist theology, in which qualities and characters of the community were strictly identified as feminine and separate from masculinity. Oboler notes that Wiccan communities were shifting away from exclusive, essentialist understandings of gender while LGBTQ+ individuals were pushing for the right to marry and rights of safety and security that many still do not have to this day.

Christine Hoff Kraemer furthered this argument in 2012, highlighting how more religiously and politically conservative Pagan communities may be openly homophobic or transphobic against those violating strict gender norms. Although both Kraemer and Oboler argued that communities are recognizing and dismantling this gender essentialism, Illinois Wesleyan University student Carly B. Floyd highlighted seven years later how Wicca still reinforces strict gender roles of women as mothers and nurturers. As a fertility religion, it also struggles to recognize and celebrate women’s power outside of the generative potential of motherhood, creating a queerphobic environment.

In much the same way, gender essentialist dialogue and ritual in witchcraft furthers ableism and racism. As a disabled woman myself, I have not experienced a period in years, so rituals like Cerince’s reinforce the idea that the magic within my body and those of other people not having periods has run dry or does not exist. This dialogue also harms nonbinary folx and trans men who still face discrimination and erasure within some feminist and anti-choice groups, and within a broader culture that continues to gender menstruation and period products. For people with endometriosis, PCOS and ovarian cysts, for example, their ovaries, uterus, and vulva may be a source of significant pain and suffering. This kind of gender essentialist dialogue — emphasizing the beauty and magic of being able to menstruate and have children — fuels toxic positivity and ableism and is a common ableist tactic among doctors who argue against relief in favor of procreation.

Witchcraft has often also been associated with racism, deployed through an academic and colonial othering. Racism itself has been described by Aph Ko as a zoological witchcraft that essentializes the experiences of the oppressed, in much the same way that covens and communities essentialize experiences of gender. The Goddess Worship movement that Cerince is part of is currently experiencing a renaissance in the Americas and Western Europe, and it is not a coincidence that most of the people showcasing these rituals have white skin and bright red blood.

BIPOC individuals also experience period shaming and sexism, but the argument that every witch’s experience of race is the same or that racial equality exists in the witchcraft community is categorically untrue and harmful for BIPOC community members, art historian and interdisciplinary artist Kevin Whiteneir Jr. argues. Every type of essentialism, from gender to race and sexuality, harms the witchcraft community because Wiccan, Pagan, and Goddess Worship groups were created as a refuge for those seeking disruptive, diverse, and radically inclusive spiritual spaces and communities. They were communities created to affirm and welcome.

Cerince posted a poem on May 4, 2023 that ended with the words, “when patriarchy falls/ only She will remain.” But this framing excludes queer magic practitioners, like Whiteneir and Edén, from the future of witchcraft, from the future of the communities they contribute to and sustain. The bodies of trans, nonbinary, and disabled individuals and people of color are no less sacred than Cerince’s body; rather, it is her commitment to gender essentialism and the essentialism of other blood magic witches that challenges her community’s strength and limits the magic it contains.

Emma Cieslik (she/her) is a queer, disabled religious scholar and public historian based in Washington, DC. She is a graduate of Ball State University with a Bachelor of Arts in Public History and Biology, and George Washington University with a Master of Arts in Museum Studies.