Herstory: Jewishness in/and Feminist Discourse

By Sarah Emanuel.

Socio-narratologist Arthur Frank writes that “stories animate human life” (see Letting Stories Breathe). They tell us how to make sense of our surroundings, how to develop relationships with those around us, and how to decide what—and who—matters. In fact, we as a species have been able to develop and diversify at such a rapid pace largely because of our ability to tell stories (see Podcast on Human Development).Through storytelling, we cannot just make sense of past experiences and move forward, but also foster collective identity, imagine alternative futures, and, indeed, survive (see Your Storytelling Brain and Science Behind Storytelling).

Feminist discourse is built on stories, too. In the 1960s and 1970s, women fighting for liberation started creating more rapidly “herstories”—narratives that protested male dominated understandings of society by offering descriptions of female history and heritage (see Public Women, Public Words). Indeed, because of the oppressive experiences women have shared—and the counter-narratives they have told—the feminist movement has grown to recognize not just harmful male-female oppositions, but also intersecting categories of oppression such as sex, race, and class.

In short, stories tell us what we can and cannot do, what we should and should not change. And if there is one thing feminist criticism teaches us, it is that we need to take seriously the stories we tell. So perhaps it is time I put these words into action, and share my own:

When I was a first-year doctoral student, my Women’s and Gender Studies professor asked our class to get into groups based on race and sex. “For the next 15 minutes,” she announced, “gather into groups of White Men, White Women, Non-White Men, and Non-White Women, and talk only amongst those within your own group.”

The assignment was designed for us to understand more affectively certain social privileges, and to grasp more fully the theory behind intersectionality—the theory that categories such as race and sex contribute in unison to systems of power and, as such, our own experiences (see NewStatesman and White Privilege and Male Privilege). For example, because I am White, I can expect persons with my color skin to be represented in societal discourse. But because I am a woman, I am often at the same time not taken as seriously or given as much representation as my male counterparts.

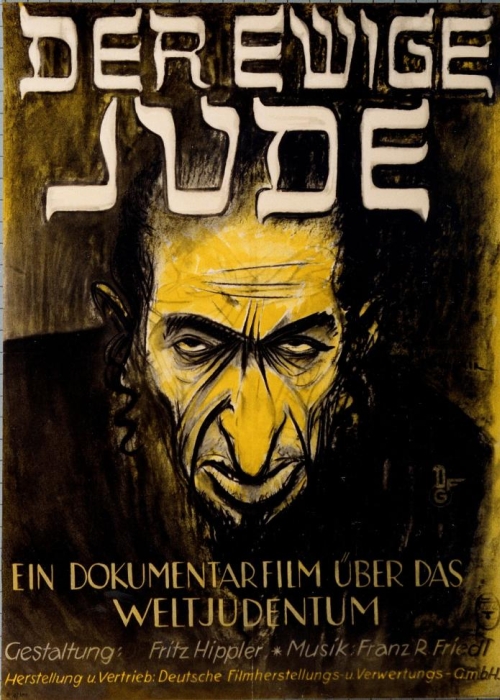

Despite how much I needed to recognize my White privilege in class that day, I still stood in-between the White and non-White Woman circles, numb. I couldn’t move. I was the only female Jew in the building and, as such, wondered what to do about the literature of the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries that marked the Jew as having blackened and diseased skin. Physiognomic features such as the big nose, big lips, and protruding mouth were also thought to help persons recognize Jews as black and/or non-White without having to resort to skin pigmentation (The Jew’s Body). These very ideas gave rise to the racial extermination of 6 million Jews in the Holocaust. Members of my family died with them. Members of my family were not White.

But the Holocaust is over, right? Jews who have light-toned skin, like me, are now considered White, right (see Whiteness of a Different Color)? After all, as I stood numb between the two groups of women, I knew that I benefitted unfairly because of my skin color on an hourly basis. Such knowledge has been confirmed repeatedly by the American racial climate post Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner, and, more recently, Michael Brown and the Ferguson riots (see Race/Off and Ferguson Despair). So why couldn’t I move? Why did I feel so different? And why am I only now, post-Black Lives Matter, choosing to talk about it?

I find Evelyn Torton Beck’s 1998 article, “The Politics of Jewish Invisibility,” to most adequately give words to my discomfort that day (Torton Beck). In her view, the Jew does not yet fit into our interlocking categories of sex, race, and class, and so therefore often feels invisible in certain feminist conversations. She writes that, while our intersecting vocabulary

Has allowed us to stretch ‘sex’ into ‘sexual difference’ and ‘race’ into ‘ethnicity,’ it has failed to allow us to account for the Jew, who cannot be made to fit into the pre- existing categories. ‘Jew’ describes a variety of factors (including but not limited to the intersection of religious identity, historical, cultural, ethical, moral, and linguistic affinities).

In other words, even when I took into consideration the expansion of the assigned categories “race” and “sex,” the Jewish invisibility in the classroom made it seem as if I did not belong anywhere. To fit without hesitation into the White group would have meant to disregard portions of my family history that involved oppression on the basis of not actually being White. It would have meant to leave behind my Jewish cultural memory in favor of a theoretical construct that didn’t seem to consider a wide enough spectrum of lived experience. For while I certainly receive undeserved privilege because of the color of my skin, the category “White” does not expand to include all parts of my racial identity, which, based on conflicting constructions of race, seems to actually be neither white nor non-white (or maybe both?), anyhow.

To conclude, I fear, even as I type, what it might mean to publicly acknowledge my confusion about Jewishness within an intersectional conversation. But feminism, including feminist conversations within the Black Lives Matter movement (see A Herstory), has taught me to tell stories—even if (especially if) I am afraid. For if the Jew doesn’t fit our categories, it is likely other “Others” don’t, either (see Torton Beck).

It’s been nearly 20 years since Torton Beck wrote her article, and, still, the categories have not shifted. My goal here has been to add story to her theory, in hopes that it might create space for further conversation. After all, we are the stories that we tell. They create us. They shape us. They push us (and feminism) forward. Perhaps sharing more stories can help us realize that, if the categories we use do not leave room for “Other” stories to be told, then it is the categories—not the stories—that should be reconsidered.

Sarah Emanuel is a PhD candidate in the Graduate Division of Religion at Drew University, where she focuses on New Testament/Early Christianity with a concentration in Women’s and Gender Studies. Her secondary research foci include: Second Temple and Early Judaism, Biblical Narrative/Storytelling, The Bible and Theory, and Ancient Jewish-Christian Encounters. Sarah currently teaches in the Religion Department and Core Curriculum at Seton Hall University. She also leads two Rosh Hodesh groups through Moving Traditions, which focus on the impact of gender and gender theory on Jewish teens. When she is not teaching, Sarah is working on her dissertation, “Roasting Rome: Humor, Resistance, and Jewish Persistence in the Book of Revelation.”